Introduction

The final third of the 19th century witnessed a convergence of rapid social change, technological innovation, and a sporting revolution across England. As football (soccer), cricket, and rugby shifted from informal, local pastimes into codified, nationally beloved sports, a parallel transformation was occurring in the material culture of fandom: the rise of the sports card. Originally emerging from the established Victorian trade card tradition, sports cards during the period 1870–1900 evolved through successive advancements in printing, artistic representation, distribution, and collecting practices to become potent markers of sporting culture and social aspiration. This report provides an exhaustive account, supported by contemporary research and historical evidence, of how sports cards relating to English football, cricket, and rugby originated, were manufactured and traded, and ultimately helped shape both the collectible industry and popular imagination.

Historical Context: Sport and Society in Late Victorian England

To understand the emergence of sports cards, it is essential to appreciate the broader context of sport’s ascendance in Victorian culture. The period from 1870 onwards saw the codification of rules, the birth of nationwide competitions (such as the FA Cup in 1871), massive increases in popular press coverage, a surge in literacy through educational reforms, and the rise of the leisure industry. Football, cricket, and rugby were at the vanguard of this revolution and embodied the era’s ideals of rational recreation, muscular Christianity, and national identity.

The popularity of sport was nurtured by evolving urban culture, the establishment of sporting clubs, and the commercialization of both leisure and fandom. The platforms for this commercialization included not just stadiums and periodicals, but increasingly, mass-produced objects—chief among them, the sports card.

Origins of English Sports Cards (1870s–1900): From Trade to Sports Depiction

The lineage of the 19th-century sports card traces directly to the Victorian 'trade card': small, vividly printed advertisements distributed to entice customers and reinforce brand loyalty. Trade cards proliferated as printing technology advanced and the consumer market expanded, with initial subjects ranging from shopfronts and products to fanciful scenes and, gradually, portraits of public figures.

By the 1870s and 1880s, the tradition of trade cards had matured; tobacco companies and merchants were embellishing cards with ever more elaborate illustrations, mirroring both the increased sophistication of color printing (especially chromolithography) and a public thirst for imagery and collectibles. The initial sports cards appeared with all manner of trade goods such as biscuits, drinks & perfume. Huntley & Palmer being one notable example. Only slowly did British issuers—lagging behind American tobacco companies such as Allen & Ginter—begin to depict sports figures and teams. While American cards first showcased baseball in the late 1870s, it was not until the early 1880s that English companies, principally outside London, pioneered cards focused on cricket, football, and rugby players and teams.

Central to this nascent industry were the regional innovators clustered in Yorkshire—catalyzed by both local enthusiasm for sport and access to cutting-edge lithographic printing.

Key English Manufacturers and Producers: The Yorkshire Nexus

John Baines of Manningham Litho, Bradford

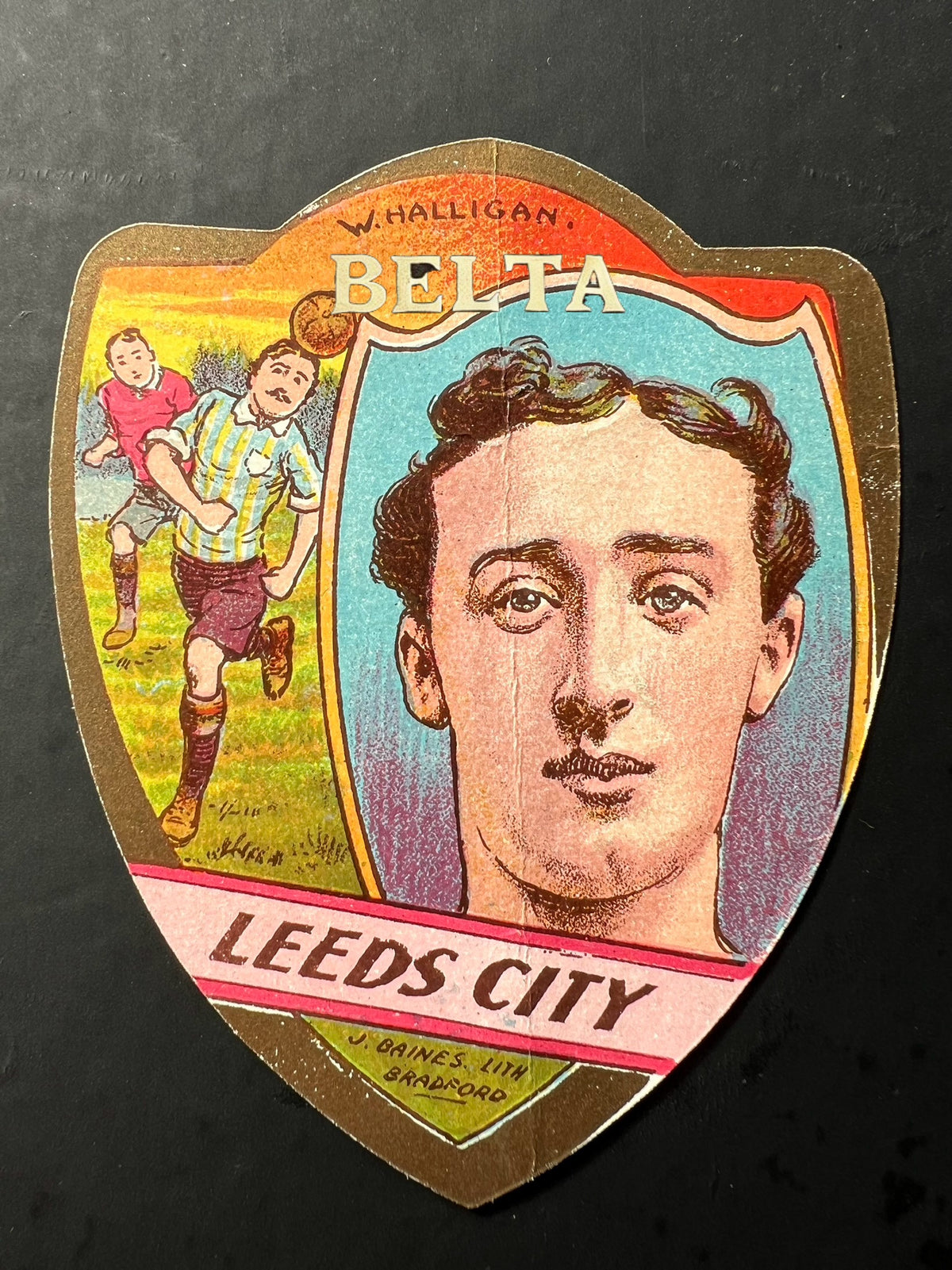

The single most influential figure in the earliest phase of English sports card manufacture was John Baines, known as the "Football Card King." Operating from Manningham, Bradford, as a lithographer rather than a printer, Baines initiated production around 1882–1883, outsourcing the final print runs to major Yorkshire printers such as Alf Cooke of Leeds, as well as Berry Brothers and Richardson.

Baines's ingenuity lay not only in securing compelling illustrations of sporting heroes but also in his development of distinctive die-cut card shapes (shields, hearts, fans) and the deployment of novel marketing strategies—such as 'Lucky Bags,' prize redemptions, and competitive collecting incentives geared at children and young fans.

Competitors and Collaborators

The success of Baines spawned numerous rivals, notably:

- James Briggs of Leeds who produced similar cards (famously the 1886 Arthur Wharton card), sometimes pirating or adapting Baines’s designs.

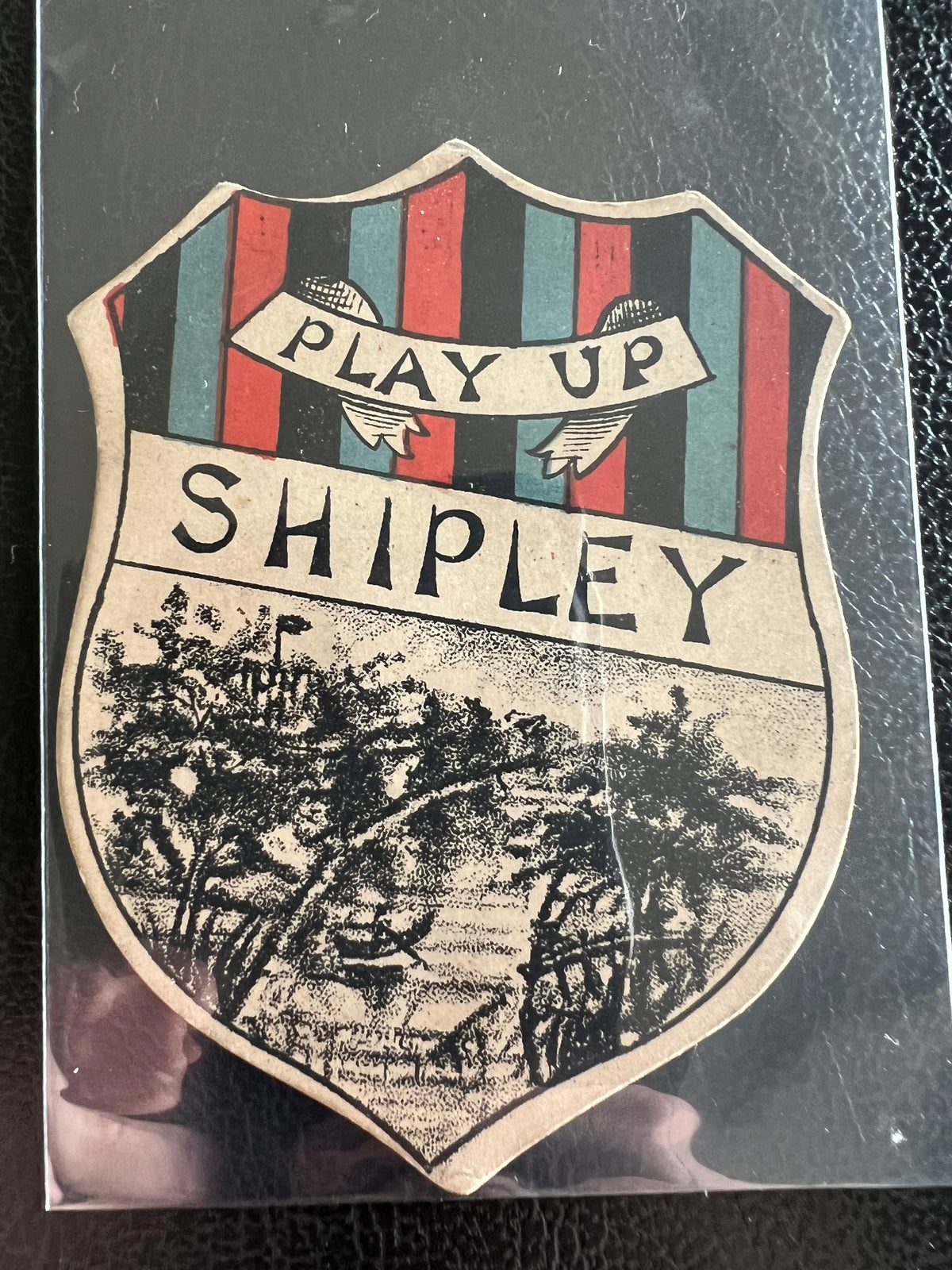

- W. N. Sharpe of Bradford, who entered the football card market in the late 1880s with "Play Up!" cards.

- Alf Cooke (printer), pivotal in the physical manufacturing of cards for both Baines and Briggs.

- Other regional small publishers: Ormerod Brothers, Brown Litho, and Berry Brothers also contributed to the early spread of football, rugby, and cricket cards, often with overlapping roles as designers, printers, or distributors.

The emergence and decline of smaller manufacturers were typical, with Baines maintaining dominance through relentless innovation, legal protections (patents), and aggressive acquisition of competitors’ stock and designs over time.

Printing and Manufacturing Techniques (1870–1900)

Lithography and Chromolithography: The Foundation of Mass Visual Appeal

The workshop technique most associated with late 19th-century sports and trade cards was color lithography, or more specifically, chromolithography. Developed in the early 19th century and perfected by mid-century, chromolithography allowed for the production of brilliantly colored illustrations through successive pressings from multiple stones or plates, each carrying a different color.

The process began with an artist's sketch (often in watercolor), which would then be transferred by an etcher onto the lithographic stone. For every color present in the final image, a separate stone was required. For fine, multi-color cards, this could mean up to a dozen print runs per card, each pass carefully aligned to build up the full image layer by layer. This method was especially well-suited to the vibrant club colors and team crests so crucial in sporting representation.

- Hand-engraving and drawing provided often-naïve, highly stylized depictions but lent a personal, almost artistic charm to each card—no two printings looked exactly the same in detail.

- Heavy use of stipple dots, solids, and shading allowed for both bold outlines and subtle textures.

Card Stock and Die-Cutting

Early sports cards in England were not restricted to rectangle shapes; Baines, in particular, used shield, heart, fan, and ball shapes, cut with precise die tools from sheets of card stock. Simple, rounded shields were easiest and most durable; intricate shapes such as octagons and fans, while visually arresting, bent or tore easily and were rarer survivors.

The backing card was typically thin, medium-quality pasteboard, with some improvements in thickness and finish for later cards (1890s onward). Card backs were often left blank, bore manufacturer stamps (such as Baines's cigar shop rubber stamp), or advertised products (notably Pears Soap and Halstead's Ointment, both frequent Baines advertisers).

Design and Artistic Representation

The visual language of these cards was instantly recognizable—bold team colors, stylized crests, simplified player likenesses, or sometimes only the name and a trophy or ball. Famous players such as W. G. Grace were depicted with a Union Jack or club emblem, and from 1886–7 onward, more lifelike figure images began to emerge, sometimes commemorating athletic feats (e.g., Arthur Wharton’s world-record in sprinting).

Later in the 1890s, advances allowed for more intricate border work, gold medal motifs, and distinguishing backs, but throughout the era, the style remained exuberant, clear, and direct.

Major Card Sets, Standout Examples and Key Milestones

The following table summarises leading sets, manufacturers, and sports represented during the core 1870–1900 period:

- Shield-shaped football cards | John Baines, Manningham | Football, Rugby | Arthur Wharton, Fred Bonsor, local teams | 1883–1900+

- Club & Triangle cricket cards | Baines / Alf Cooke (Leeds) | Cricket | W. G. Grace, Jack Blackham, Fred Spofforth | 1883

- Octagonal-shaped cricket cards | Baines / Alf Cooke | Cricket | Australian tour (1st Ashes Test commemorative)| 1883

- Fan-shaped “football” cards | Baines (with patent 13173) | Football/Rugby | Arthur Wharton, club selection | 1886–1888

- Heart-shaped cards, Pears Soap | Baines | Football, Rugby | Club crest, club name, Pears Soap adverts | 1885–1888

- Large shield cards, “Football King” | Baines | Football, Rugby | W. G. Grace (shield), Frank Sugg | 1887+

- “Play Up!” football cards | W. N. Sharpe (Bradford) | Football | Amateur, local and professional clubs | 1888–1895

- Football shields (pirated) | James Briggs (Leeds) | Football | Arthur Wharton copied card | 1886–1887

- “Cup Ties” back cards | Baines | Football, Rugby | Linked to annual competitions | 1886

- Rectangular rugby commemoratives | Baines | Rugby | Home Nations teams, Queen’s Jubilee | 1890

- Miscellaneous local cards | Ormerod Bros, Brown Litho | Football, Rugby | Minor team cards, hotel sponsors | 1880s–1890s

We have number of J Baines cards for sale here:

https://beltacards.com/collections/baines-shields

Key examples with significant historical/value milestones—include:

- Arthur Wharton Baines/Briggs Football Card (1886): The earliest-known card depicting a football player, and the first professional black player featured. Only two known examples; one auctioned in January 2024 for over £33,500 GBP, making it the most valuable football card sold in the UK to date.

- W. G. Grace Cricket Cards (1883): Both Union Jack and club variants, among the first cricket cards ever produced—Grace’s cards now trade for five-figure sums and are considered central artefacts of sporting and collecting history.

- Fan-shaped club series (circa 1887): Patented shapes, vivid player/team combinations, and imaginative representation—precursors of themed set collecting.

Distribution and the Trade Card Economy: Tobacco, Soap, and Surprises

A key innovation in the late-Victorian sports card industry was the creation of distribution systems that linked cards to ordinary consumer goods or to blind-packed novelty. Two principal channels dominated:

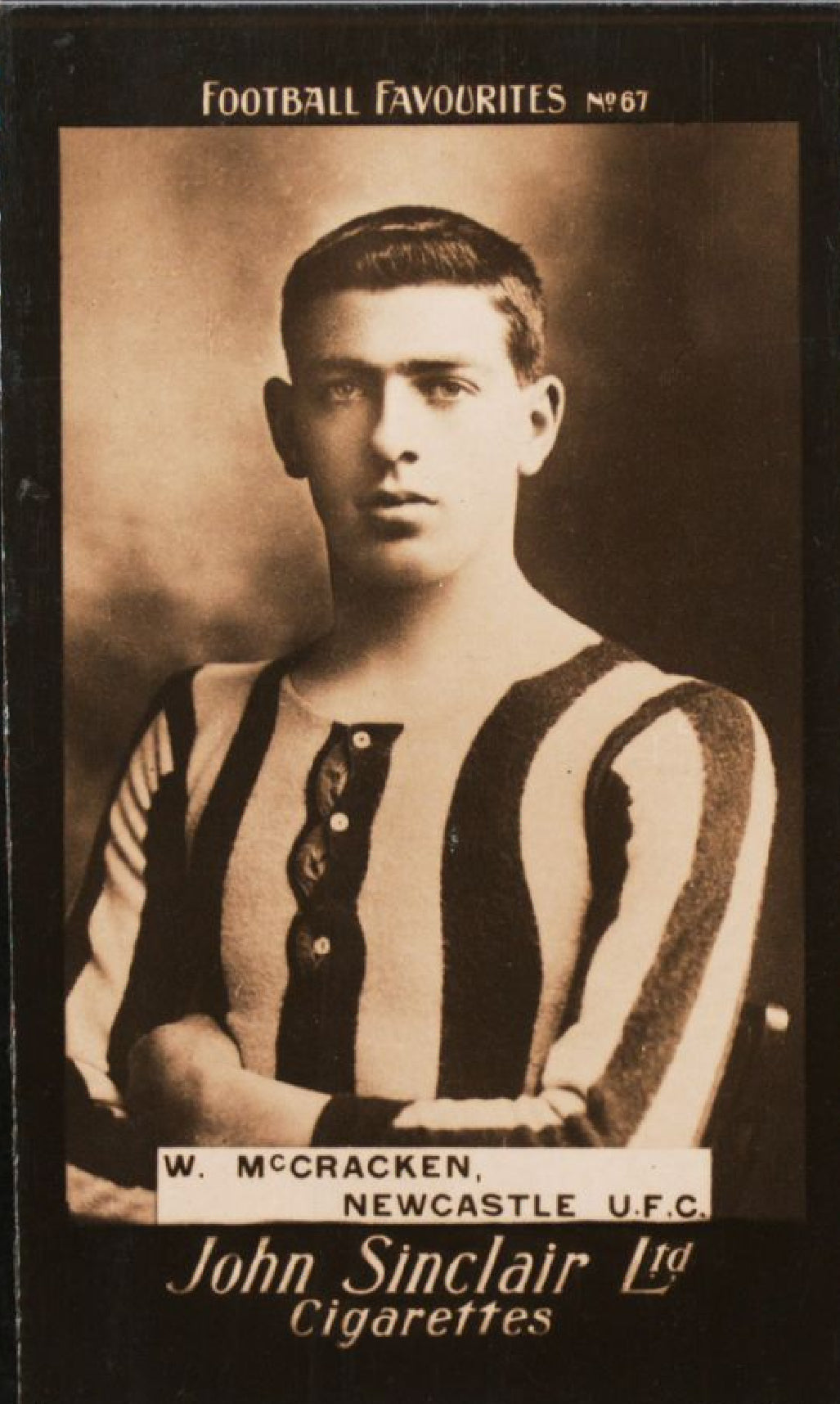

Tobacco and Trade Cards

Tobacco companies discovered the value of inserting cards into packets—both to reinforce the packaging and, more importantly, to foster brand loyalty and serial purchasing (as buyers sought to complete sets). While the earliest English sports cards were more often associated with lithographic packets and local distributions (rather than mass tobacco inserts, unlike the US), the late 1890s did see tobacco and trade card sets directly advertising cigarettes, soaps, and medicines.

Cards in this model often featured not only sports but also actresses, military themes, or landscapes, highlighting the commercial continuum between advertising ephemera and collectibles.

Lucky Bags, Prize Schemes, and Scrapbooks

Baines and contemporaries promoted "Lucky Bags"—blind packets sold in toy shops or general stores, containing random assortments of cards. Prize redemption was a foundational marketing tactic: collectors could exchange certain cards, or empty packets, for football jerseys, coin prizes, or other premium gifts. Some cards (concertedly rare later “listers”) were inserted in such a way that completing a set required considerable investment, spurring further purchases.

The culture of swapping and searching for rare cards became embedded, with swap systems and “who’s nearest?” skill games proliferating in schoolyards and social clubs, paving the way for the sports card as an object of communal currency.

The Collector Culture: Scrapbooks, Social Ritual, and Public Imagination

The Victorian Scrapbook Craze

From the 1870s onward, collecting and album-making became a widespread pastime among children and adults alike. Trade, advertising, and later sports cards, along with embossed “scraps,” would be glued, clustered, and displayed in elaborate albums, serving both as memory objects and status symbols.

Victorian enthusiasts shared tips for clustering cards stylishly, preserving them, and achieving an attractive display—sometimes with a distinctly gendered subculture (e.g., young women’s scrap albums were likely to contain both domestic and sporting themes). Many surviving 19th-century scrapbooks today reveal the eclectic, hybrid character of early collecting, often mixing sports, animals, product brands, and stage celebrities on the same page.

Games and Social Practices

Baines-era cards were not only collected and admired, but used in playground games—most famously, “skaging” or “who’s nearest?” (flicking cards against a wall to win a pile). This activity both fostered a broader participation in collecting (not just among wealthy or studious children) and contributed to the extraordinary rarity of high-grade specimens, as cards were frequently scuffed, creased, or lost in play.

The Card as Social Marker and Ephemera

Cards reinforced the social significance of sport, allowing fans to “wear” allegiance by affixing cards to hats or clothes at matches (a fashion reported in Bradford as early as 1884). Meanwhile, the act of collecting itself became entwined with the competitive, aspirational ethos of the age: completion of difficult sets, especially to win a coveted football jersey or musical box from Baines’s prize pool, was a mark of both perseverance and luck.

Cultural Impact and Representation

The sports card was not merely a commercial trinket or printed afterthought; it captured, and in turn shaped, public perceptions of sporting identity, social mobility, and the virtues of team and hero worship. Several elements of cultural significance are evident:

Hero Worship and the Democratization of Fame

Cards elevated players—often regional or local team members, but sometimes the likes of W. G. Grace or Arthur Wharton—to the status of popular icons. Children in the industrial north could collect and discuss cards of the “fabulous” Arthur Wharton or the “Babe Ruth of Cricket” Grace, cementing a new, democratized celebrity culture tied to athletic achievement.

For players of color or working-class background, such as Arthur Wharton, appearing on a card at the national level offered a measure of cultural legitimacy that extended beyond the pitch, even as barriers of race and class persisted elsewhere.

Class, Aspiration, and Social Ritual

The structure of collecting—prizes, swaps, the pursuit of elite “listers”—mirrored the competitive ethos of Victorian society and its dreams of upward mobility. The very ability to keep or complete an album, or present a full card set for redemption, reflected a family’s disposable income, a child’s perseverance, or sometimes, a parent’s occupation (newsagents’ children often had an advantage!).

From Ephemera to Heritage

In later decades, the cultural afterlives of these cards have only grown. Today, original Baines, Grace, or Wharton cards are sought by private collectors, displayed in museums such as the National Football Museum, and sell at auction for tens of thousands of pounds—testaments to their role as both trivial ephemera and touchstones of sporting heritage.

Timeline of Key Milestones and Trends (1870–1900)

- 1870s: Growth of pictorial lithography and advertising cards but limited sports-specific issues in England.

- Early 1880s: John Baines, Manningham Litho, begins producing team and player cards in shield and novelty shapes for cricket, rugby, and eventually football.

- 1883: Cricket cards featuring W. G. Grace, Fred Spofforth, and others issued by Baines, often commemorating club and international competitions.

- 1884: Evidence of sports card “fashions” at matches; cards used as wearable fan accessories.

- 1886: The epoch-making Arthur Wharton card; recognized as the world's first football card depicting a named soccer player.

- Late 1880s: Introduction of more elaborate shapes (fan, heart, oval), patent protection on novel card forms, piracy and aggressive market consolidation by Baines.

- 1890s: Rectangular, large-format rugby commemorative cards; increased use of gold medal motifs and specialized back designs.

- 1897: Patent number 197161 appears on cards; further design complexity.

- 1900: Baines’s shield card remains standard; parallel growth in tobacco-issued cards and the nascent Edwardian sets that would dominate the early 20th century.

Auction Records and Modern Valuations

Rarity is often linked not only to original production numbers but also to the heavy handling (play, pasting, swapping) which has left precious few in top condition. Cards depicting pioneering athlete/figures of color, celebrated internationals, or now-defunct local teams routinely fetch the highest premiums.

The Evolution of Artwork and Design: Aesthetic Milestonesi

From the earliest utilitarian cards—team names and basic graphics, often in a single color on shield-shaped die-cuts—to elaborate multi-color illustrations, the period from 1870–1900 saw:

- Increasing sophistication in representation: Starting from ball or shield motifs and Gothic scripts, cards evolved to depict actual player likenesses, often in club attire, and club or national flags.

- Advances in chromolithography enabled new types of shading, highlights, and pastel vibrancy. This mirrored broader Victorian visual culture, where advertising ephemera became a site of artistic innovation.

- Distinctive thematic series, such as fan-shaped cards for club captains or commemorative sets celebrating international tournaments, showed increasing awareness of the “set” as a desirable object—paving the way for the later, highly organized cigarette card series issued from the 1890s.

- Back design innovations: Starting with blank or simply rubber-stamped backs, manufacturers elaborated gold medal motifs, elaborate product adverts, and eventually standardized 'slip-in' album-compatible formats by the 1900s.

Advertising and Marketing Strategies: Innovation and Impact

Key to the proliferation of sports cards was the astute use of promotional strategies:

- Lucky Bags: The random, blind-purchase model stoked the collecting impulse, and the potential to uncover rare cards gave an edge of excitement akin to gambling (in fact, some legal controversy arose over the “lottery” nature of prize schemes).

- Redemption Schemes: Direct inducements to “collect them all” with the promise of cash or goods produced both fierce competition and enduring nostalgia among collectors.

- Cross-promotion: Cards packaged with consumer products—soap, tobacco—ensured that brands became inseparably linked with sports fandom, with Pears Soap and Halstead’s Ointment among the best documented partners.

- Children’s culture: The cards’ affordable price point (half penny per packet in Baines’s era) extended collecting well beyond the wealthy and created a lasting association between children, sport, and collection.

The Move Toward the 20th Century: Legacy and Influence

By the turn of the century, sports cards had evolved into an integral part of the commercial, artistic, and social fabric of English life:

- Cigarette card series began to dominate the market in the 1890s, soon giving rise to formally published, numbered, and album-compatible sets by companies such as Ogden’s, W.D. & H.O. Wills, and John Player & Sons.

- The collecting impulse —begun with Baines’s premiums and innovative designs—became formalized and global, influencing later trading cards, including the American bubble gum cards of the 20th century and the modern collectibles market.

- Transition to secondary market: As original card production declined or shifted toward tobacco companies, earlier Baines and associated cards became prized vintage collectibles, recognized for their historical and cultural importance.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of Victorian Sports Cards

Between 1870 and 1900, sports cards in England moved from the edge of commodity promotion to the center of popular culture, simultaneously shaping and reflecting the ways Victorians engaged with the emergent world of organized sport. Through technological mastery, savvy marketing, and a keen understanding of the community’s aspirations, pioneers such as John Baines created artifacts whose resonance has survived for a century and a half.

Today, Victorian sports cards are more than rare relics: they are invaluable artifacts of sporting history and Victorian social life, offering insight into early hero worship, industrial craft, and the rise of a mass culture of play and aspiration. The images of Grace, Wharton, and their contemporaries—cut in bright color, shield-shaped or fan-shaped, sometimes pasted lovingly into albums or flicked against pub walls—remain, in every sense, the foundations of sports card collecting and a testament to the power of sport to inspire, connect, and endure.

In summary, the late Victorian era’s sports cards were not only vehicles for commercial purpose and childhood pleasure but also mirrors of a changing society—one in which sport, commerce, and creative aspiration wove together an enduring template for how we experience, remember, and celebrate the games we love.